When Does Tabular RL Actually Break?

ax + b = c? We systematically test tabular Q-learning, SARSA, PPO, and neural baselines to find the exact complexity threshold where RL breaks. Spoiler: it's embarrassingly low—depth-2 equations (~8th grade algebra). Even with 50,000 training episodes and neural encoders, solve rates stay below 5%. The problem isn't sample complexity—it's that flat representations can't capture compositional structure.

The Question

Modern AI systems like AlphaProof, Harmonic's Aristotle, and AxiomMath's AxiomProver can tackle most International Math Olympiad or Putnam problems alike, with ease. Meanwhile, I wanted to know: what's the simplest math problem where reinforcement learning completely falls apart?

Not because scaling up is impossible (obviously throw enough compute and you can brute-force anything), but because I wanted to understand the fundamental failure modes. Where does the representation break? Is it a data problem or an architecture problem?

So I picked the most trivial symbolic task I could think of: solving single-variable linear equations.

2x = 4 # depth-1: one operation 3x + 5 = 11 # depth-2: two operations 2x - 3 = x + 7 # depth-3: three operations

The task: given an equation, apply algebraic rewrite rules (like "move constant across equality" or "divide both sides by coefficient") until you isolate x.

High schoolers solve depth-3 equations in their sleep. Can RL?

The Setup

Environment

Each equation is represented as an abstract syntax tree (AST). The agent sees the equation as a string (e.g., "Equals(Mul(Const(2), Var(x)), Const(4))") and picks from a set of rewrite rules:

divide_linear:kx = c→x = c/kmove_const_l_to_r:x + b = c→x = c - bcombine_like_terms:ax + bx→(a+b)x- ...and a few more

Episodes end when the agent reaches a solved form (x = k) or hits 100 steps. Reward is +1 for solving, 0 otherwise (I also test with reward shaping but it doesn't help).

Agents

I tested four approaches:

- Tabular Q-learning: Standard ε-greedy with string-based state representation

- SARSA: On-policy variant, same representation

- PPO: Policy gradient with GRU encoder over the stringified AST

- Random baseline: Uniform sampling over valid actions

All agents use action masking to only select valid rewrites at each step (no illegal moves).

Initial Results: Complete Failure at Depth-2

I trained each agent for 20,000 episodes on equations of varying depths. Here's what happened:

| Agent | Depth-1 | Depth-2 | Depth-3 | Depth-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPO | 38% | 19% | 4% | 1% |

| Q-Learning | 4% | 5% | 4% | 1% |

| SARSA | 4% | 5% | 4% | 1% |

| Random | 4% | 5% | 1% | 1% |

PPO does better on depth-1 (38%), but by depth-3 it's back to random performance. And depth-2? A measly 19%.

Why? The obvious hypothesis: state sparsity. Because states are represented as raw strings, "Equals(Mul(Const(2), Var(x)), Const(4))" and "Equals(Mul(Const(3), Var(x)), Const(6))" are treated as completely unrelated—even though they have identical solution structure.

The Q-table almost never sees the same state twice, so it can't propagate value. The agent is just doing a random walk through valid actions.

The Investigation: Data vs. Representation

But wait—is this a data problem or a representation problem?

Maybe 20,000 episodes isn't enough. Maybe the agent just needs more experience to stumble into the right patterns. Or maybe the representation is fundamentally broken and no amount of data will help.

To test this, I ran two follow-up experiments:

Experiment 1: Coefficient Normalization

What if we explicitly remove the coefficient information? Instead of treating 2x = 4 and 3x = 6 as different states, normalize them both to C·x = C (where C is a placeholder for any constant).

This should massively reduce state space. For depth-1 equations, the state space collapses from ~341 unique states down to just 2.

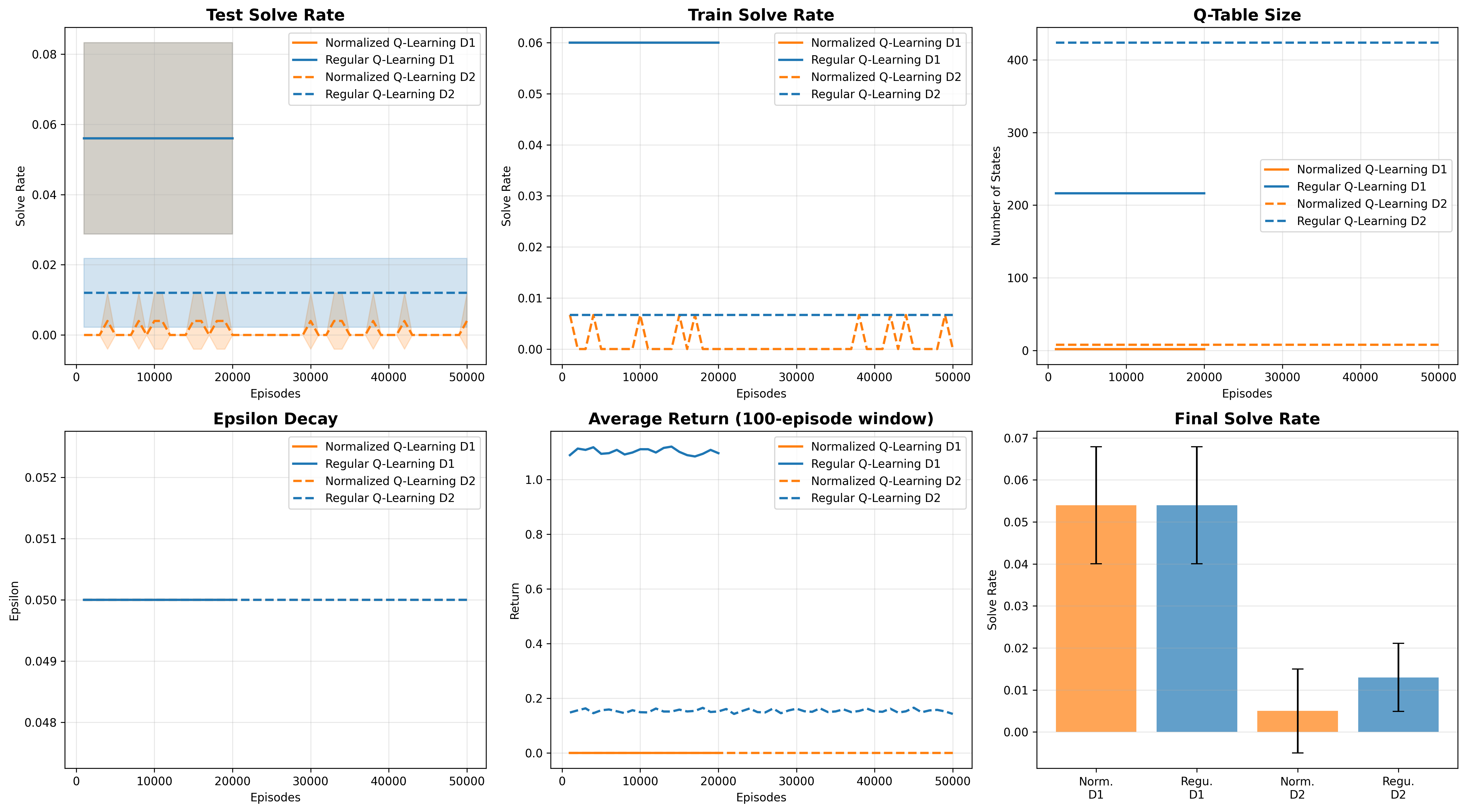

I trained normalized Q-learning for 50,000 episodes (2.5× more data than before).

| Method | Depth | Episodes | Solve Rate | Q-Table Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Q-Learning | 1 | 20K | 5.4% ± 1.4% | 341 ± 7 |

| 2 | 50K | 1.3% ± 0.8% | 673 ± 13 | |

| Normalized Q-Learning | 1 | 20K | 5.4% ± 1.4% | 2 ± 0 |

| 2 | 50K | 0.5% ± 1.0% | 8 ± 0 |

So state abstraction helps efficiency, but doesn't overcome the compositional barrier. The problem runs deeper.

Experiment 2: Neural Baseline (GRU Encoder)

Maybe the problem is that any flat string representation is doomed. What if we let the agent learn its own representation?

I implemented a minimal neural baseline:

- Character-level GRU encoder: Maps equation strings to 64-dim embeddings

- MLP Q-network: Predicts Q-values from (state embedding, action encoding)

- Experience replay: Batch size 32, buffer size 10K

This is basically DQN with a sequence encoder. The GRU can theoretically learn to group similar equations and discover algebraic patterns.

After 500–1,000 training episodes:

| Method | Depth-1 | Depth-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Tabular Q-Learning | 5% | 1% |

| Neural Q-Learning (GRU) | 10% | 4% |

Why Does This Happen?

The extended experiments rule out sample complexity. Even with:

- 50,000 training episodes

- 99% state space compression via normalization

- Learned neural representations

...the agents still can't solve depth-2 equations (<5% solve rate).

The problem is representations that don't capture compositional structure.

State Sparsity Isn't the Whole Story

Yes, tabular methods see too many unique states. But even when we fix that (via normalization), performance doesn't improve. Why?

Because ax + b = c requires a sequence of dependent operations:

- Move

bto right side →ax = c - b - Divide by

a→x = (c - b)/a

A flat string representation can't expose this dependency. The agent has no way to know that "the thing I do now affects what rewrites are possible later."

Why Neural (GRU) Also Fails

The GRU can learn some patterns (hence the 2–4× improvement), but it induces a syntax-level embedding without algebraic invariance. It might learn heuristics like "apply divide_linear near the end," but it can't systematically decompose multi-step problems.

To do that, you'd need representations that expose:

- Tree structure (AST hierarchy)

- Algebraic equivalences (e.g.,

2x = 4≈3x = 6) - Operator composition (which operations enable which future moves)

This is why modern systems use tree-LSTMs, graph neural networks, or symbolic AST embeddings.

What Would Actually Work?

Based on these results, here's what you'd need to solve even depth-2 equations with RL:

- Tree-structured encoder: Tree-LSTM or GNN over the AST

- Symbolic priors: Hard-coded knowledge of algebraic equivalences

- Hierarchical policies: "First isolate the variable, then simplify"

- Search guidance: MCTS or beam search instead of pure RL

This is exactly what AlphaProof and similar systems do. They don't use vanilla RL—they use heavily structured architectures with symbolic reasoning baked in.

Our negative results explain why this is necessary.

Key Takeaways

- Tabular RL breaks at embarrassingly low complexity: Depth-2 equations (8th grade algebra) are essentially unsolvable.

- It's not a data problem: 50K episodes, 99% state compression, and neural encoders all fail. The issue is representational.

- Flat representations can't capture composition: String-based or sequence-based encodings miss the hierarchical structure needed for multi-step reasoning.

- This motivates structured architectures: Modern neuro-symbolic systems succeed because they incorporate tree encoders, symbolic priors, and search—our results show why these aren't optional.

Code & Reproducibility

All code is available on GitHub. The experiments ran on Azure ML with H100 GPUs (though most runs were CPU-only). Total compute cost: ~$170 for the extended experiments.

Key files:

agents/q_learning_neural.py- Neural Q-learning with GRU encoderagents/q_learning_normalized.py- Coefficient normalizationtrain_extended.py- Extended training script (20K–50K episodes)run_cluster.py- Parallel execution across seeds

What's Next?

This was originally a course project, but I think the negative result has value—it establishes a minimal complexity threshold where standard RL methods break.

Possible extensions:

- Implement tree-LSTM baseline to confirm structured encoders fix the problem

- Test LLM baselines (Llama via Ollama) for comparison

- Extend to quadratic equations or simple integrals

But the core lesson is clear: without structural priors, RL can't even solve high school algebra. And that's worth knowing.

Thanks for reading! This work originated as a final project for 6.7920 (Reinforcement Learning, Theory and Foundations). Extended experiments were run using Azure ML compute credits.